Hitler intended to start his invasion in May, but he had to divert armored forces to Yugoslavia to bail out Mussolini. That cost Hitler a month and Hitler came within a stone's throw of Moscow before he was stopped. Yugoslavia probably saved the world's ass. Originally Posted by the_real_Barleycornfinally someone that knows their history....

- texassapper

- 03-27-2022, 01:37 PM

- texassapper

- 03-27-2022, 03:57 PM

Just think if there was a no fly zone with a superpower such as The USA backing it. Originally Posted by Jackie S? DO YOU UNDERSTAND WHAT THAT EVEN MEANS????

A no-fly zone is enforced.... and if the Russians fly into that airspace... it means US aircraft (or NATO) must SHOOT DOWN the Russian aircraft.

That's called a casus Belli (an act of war). yeah I can image EXACTLY what that would look like...

For Ukraine? FTS.

- Jackie S

- 03-27-2022, 05:34 PM

[QUOTE=texassapper;1062794423]? DO YOU UNDERSTAND WHAT THAT EVEN MEANS????

A no-fly zone is enforced.... and if the Russians fly into that airspace... it means US aircraft (or NATO) must SHOOT DOWN the Russian aircraft.

That's called a casus Belli (an act of war). yeah I can image EXACTLY what that would look like...

For Ukraine? FTS.[/QUOTE

We have enforced no fly zones in quite a few “wars” since WW-2 ended. Of course, none of the Countries involved had enough power to challenge us.

Call Putin’s bluff. Tell him we are taking the air war out of the equation. Let the ground forces fight it out.

My bet is he backs down. Or some one in his close inner circle has a 9mm election.

A no-fly zone is enforced.... and if the Russians fly into that airspace... it means US aircraft (or NATO) must SHOOT DOWN the Russian aircraft.

That's called a casus Belli (an act of war). yeah I can image EXACTLY what that would look like...

For Ukraine? FTS.[/QUOTE

We have enforced no fly zones in quite a few “wars” since WW-2 ended. Of course, none of the Countries involved had enough power to challenge us.

Call Putin’s bluff. Tell him we are taking the air war out of the equation. Let the ground forces fight it out.

My bet is he backs down. Or some one in his close inner circle has a 9mm election.

- texassapper

- 03-27-2022, 05:39 PM

Do you enjoy gambling with the lives of hundreds of millions?

My bet is he backs down. Or some one in his close inner circle has a 9mm election.

You’ve been watching too many Tom Clancy movies.

- VitaMan

- 03-27-2022, 05:49 PM

Hitler intended to start his invasion in May, but he had to divert armored forces to Yugoslavia to bail out Mussolini. That cost Hitler a month and Hitler came within a stone's throw of Moscow before he was stopped. Yugoslavia probably saved the world's ass. Originally Posted by the_real_Barleycorn

Napoleon invaded Russia, and the French had to sell what is now about half of the United States to finance the war (Louisiana Purchase). If he hadn't done that, half of what is now the USA would be speaking French now. Napoleon probably helped to create what is now the USA.

yada yada yada

- Why_Yes_I_Do

- 03-28-2022, 06:19 AM

Russia Sold Its Stake in Uranium One Shortly Before Invading Ukraine – The Same Company Clintons Helped Turn Over to Russians

We knew before the 2016 Election that the Clintons made a lot of money in the sale of US uranium, owned by Uranium One, to Russia.

As previously reported, the FBI had evidence that Russian nuclear industry officials were involved in bribery, kickbacks, extortion and money laundering in order to benefit Vladimir Putin prior to Obama admin handing over 20% of America’s Uranium to Russia, according to a devastating report by John Solomon via The Hill.

Who was right in the middle of it all? HILLARY CLINTON. MILLIONS of dollars flowed to the Clinton Foundation as our Uranium rights were sold to Russia while she was Secretary of State.

The Uranium One deal was covered up by the mainstream media as they do with all corruption related to the Democrat Party. But eventually, word got out and we were reporting on the many connections to the sale of Uranium One.

Later in November of 2018, a whistleblower came to the US government with information on Uranium One. This individual tied information from the sale of Uranium One to Russia with the Clintons and other top Democrat politicians.

In late November, this individual’s house was raided by sixteen FBI agents who spent six hours at his place looking for information related to Uranium One. After this, we never heard anything further from the whistleblower.

Today we’ve uncovered that Russia sold its stake in Uranium One in November 2021 shortly before Russia invaded Ukraine. According to Russia’s state-owned energy company, Rosatom, Russia sold its stake in Uranium One in November 2021.

It looks like the Russians knew the US would take back their stake in Uranium One after their invasion of Ukraine so they sold their piece in the company before the US took it over.

Hat tip Bob Bishop

We knew before the 2016 Election that the Clintons made a lot of money in the sale of US uranium, owned by Uranium One, to Russia.

As previously reported, the FBI had evidence that Russian nuclear industry officials were involved in bribery, kickbacks, extortion and money laundering in order to benefit Vladimir Putin prior to Obama admin handing over 20% of America’s Uranium to Russia, according to a devastating report by John Solomon via The Hill.

Who was right in the middle of it all? HILLARY CLINTON. MILLIONS of dollars flowed to the Clinton Foundation as our Uranium rights were sold to Russia while she was Secretary of State.

The Uranium One deal was covered up by the mainstream media as they do with all corruption related to the Democrat Party. But eventually, word got out and we were reporting on the many connections to the sale of Uranium One.

Later in November of 2018, a whistleblower came to the US government with information on Uranium One. This individual tied information from the sale of Uranium One to Russia with the Clintons and other top Democrat politicians.

In late November, this individual’s house was raided by sixteen FBI agents who spent six hours at his place looking for information related to Uranium One. After this, we never heard anything further from the whistleblower.

Today we’ve uncovered that Russia sold its stake in Uranium One in November 2021 shortly before Russia invaded Ukraine. According to Russia’s state-owned energy company, Rosatom, Russia sold its stake in Uranium One in November 2021.

Uranium One has entered into an agreement with the American company Uranium Energy Corp. for the sale of all of the shares of its subsidiary, Uranium One Americas, Inc. (Uranium One Americas).The assets of Uranium One Americas are situated in Wyoming, and include seven uranium projects in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming and five in the Great Divide Basin. The total purchase price is comprised of $112 million in cash and the replacement (with certain corresponding payments to Uranium One) of $19 million in reclamation bonding.

The sale is carried out within the framework of the strategy of Uranium One to optimize the portfolio of uranium mining assets, aimed at increasing economic efficiency. The closing of the sale is subject to certain regulatory approvals.

It looks like the Russians knew the US would take back their stake in Uranium One after their invasion of Ukraine so they sold their piece in the company before the US took it over.

Hat tip Bob Bishop

- Jackie S

- 03-28-2022, 08:34 AM

Do you enjoy gambling with the lives of hundreds of millions?Not Tom Clancy, but reality. As in World Wars.

You’ve been watching too many Tom Clancy movies. Originally Posted by texassapper

Has history taught us nothing.

The only difference in NATO’s attitude toward Russia and Neville Chamberlains attitude concerning NAZI Germany is about 83 years, and the fact that we can kill more people more efficiently.

How many people died in WW-2. Not just soldiers, but everybody.

And it started with Hitler convincing the World that he simply wanted a few parts of Europe that in realty were German anyway.

Putin is a turd that will not flush. The only difference between him and that fat fuck that rules North Korea is Putin has a lot of nukes.

- texassapper

- 03-28-2022, 08:44 AM

The only difference in NATO’s attitude toward Russia and Neville Chamberlains attitude concerning NAZI Germany is about 83 years, and the fact that we can kill more people more efficiently. Originally Posted by Jackie SWas Chamberlain trying to expand the military alliances arrayed against Germany? No. He was not.

These are different situations which require different solutions.

How many people died in WW-2. Not just soldiers, but everybody. Originally Posted by Jackie SLess than 100 Million people... What's your point you think we can do better in round three??!!

And it started with Hitler convincing the World that he simply wanted a few parts of Europe that in realty were German anyway. Originally Posted by Jackie SAgain NOT the same situation... Russia is hardly sitting in the middle of Western Democracies and Eastern Soviets. Putin may have dreams of re-establishing the Russian empire... but he has an economy the size of Italy. Meanwhile the Chinese dragon is building a blue water Navy and laughing at the US for paying attention to Ukraine rather than where the real threat lays.

Putin is a turd that will not flush. The only difference between him and that fat fuck that rules North Korea is Putin has a lot of nukes. Originally Posted by Jackie SAnd that's exactly why if he wants Ukraine, he can have it... There's no need for the US to get in a shooting match with a nation with 3000+ nukes aimed at us.

NONE.

Ukraine is NOT a NATO signatory so we have no legal or moral obligation to come to their defense.

- Why_Yes_I_Do

- 03-28-2022, 09:50 AM

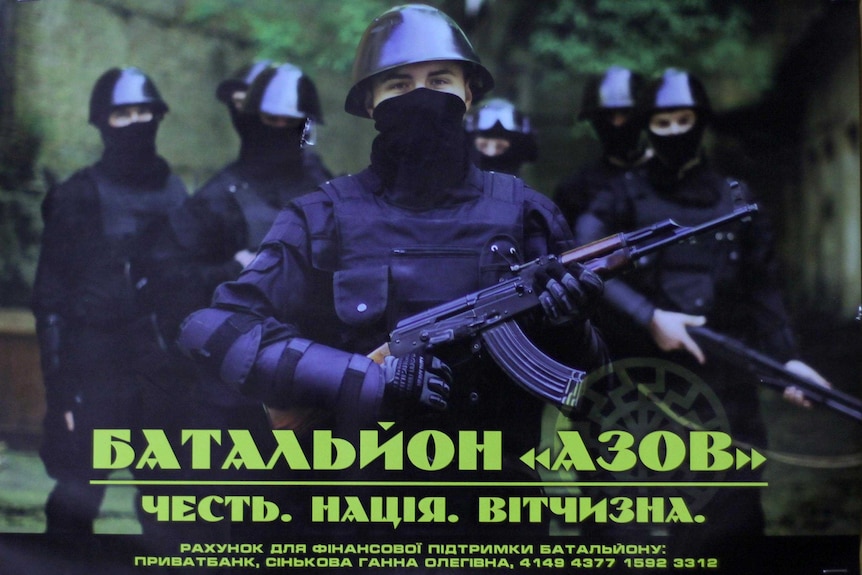

Ukraine crisis: Inside the Mariupol base of the controversial Azov battalion

The first thing you notice as you walk through the corridors of the Azov battalion's base in Mariupol are the swastikas.

There are many — painted on doors, adorning the walls and chalked onto the blackboards of this former school, now temporary headquarters for the Azov troops.

It is a confronting sight and when I query the young soldier assigned to show me around he is quick to correct me, pointing out that the symbol is in fact a "modified swastika" — more like the letter N crossed with a straight line.

When I point to another symbol of the Third Reich etched on the wall, that of Hitler's "SS", he simply shrugs and says: "We are nationalists, but we are not Nazis."

The Azov battalion is a highly controversial Ukrainian paramilitary group that has drawn much criticism for its links to the far right.

The imagery it has chosen to adopt hardly helps to allay concerns, but for my young guide it is a non-issue.

"Some journalists prefer to present us as Nazis. They look for any chance to discredit our regiment," he said.

After last month's rebel defeat of Ukrainian forces at Debaltseve in the north, attention has switched to the port city of Mariupol, less than 60 kilometres from the Russian border, which most believe is next in the separatists' sights.

I have been invited to tour the Azov base where new recruits are in training, preparing to defend the city from an attack which most here are predicting will come before the end of the Ukrainian spring.

Like pro-Russian rebels, Ukrainian soldiers rarely provide their real names when talking to journalists, using platoon nicknames instead.

The 22-year-old, 6-foot 2-inch bearded soldier showing me around is called Dancer.

A roads engineer graduate from Luhansk, Dancer joined the Azov battalion last year shortly after the armed conflict began in eastern Ukraine, attracted by the militia group's long-term goals.

"Our battalion is comprised of conscious people who have a much higher purpose than just winning the war," he said.

"We want to build a new independent and sovereign Ukraine. That's what makes us different from other military units."

The Azov battalion is a volunteer military brigade that was formed last year in Mariupol, named after the sea on which the city is located.

It is closely linked to the Social-National Assembly, an umbrella organisation to a collection of ultra-nationalist and neo-Nazi groups in Ukraine, and many of Azov's recruits are drawn by its perceived far right-wing ideology.

Currently under the auspices of Ukraine's interior ministry, there are deep concerns that arming right-wing paramilitary groups like Azov might backfire and present a future threat to the government, but Dancer says the fears are unfounded.

"The battalion operates as a professional military unit," he said.

"The commanders listen to you while you listen to your subordinates, and all the daily and military questions are solved in a democratic way.

"There is no violence against younger conscripts in Azov, no stupid orders and notations."

Azov volunteers fight alongside regular Ukrainian forces and were amongst the earliest to see action in the conflict last year and its troops have a fearless reputation.

"I wanted to join a battalion that would be on the frontline and participate in real action," Dancer said...

By Nicholas Lazaredes in Ukraine

Posted Thu 12 Mar 2015 at 7:24pm Thursday 12 Mar 2015 at 7:24pm, updated Tue 24 Mar 2015 at 6:30am

Awe, crud-buns! That was under OBama's watch. Go figure!?!

But I'm confident they are still a swell bunch-o-fellas.

The first thing you notice as you walk through the corridors of the Azov battalion's base in Mariupol are the swastikas.

There are many — painted on doors, adorning the walls and chalked onto the blackboards of this former school, now temporary headquarters for the Azov troops.

It is a confronting sight and when I query the young soldier assigned to show me around he is quick to correct me, pointing out that the symbol is in fact a "modified swastika" — more like the letter N crossed with a straight line.

When I point to another symbol of the Third Reich etched on the wall, that of Hitler's "SS", he simply shrugs and says: "We are nationalists, but we are not Nazis."

The Azov battalion is a highly controversial Ukrainian paramilitary group that has drawn much criticism for its links to the far right.

The imagery it has chosen to adopt hardly helps to allay concerns, but for my young guide it is a non-issue.

"Some journalists prefer to present us as Nazis. They look for any chance to discredit our regiment," he said.

After last month's rebel defeat of Ukrainian forces at Debaltseve in the north, attention has switched to the port city of Mariupol, less than 60 kilometres from the Russian border, which most believe is next in the separatists' sights.

I have been invited to tour the Azov base where new recruits are in training, preparing to defend the city from an attack which most here are predicting will come before the end of the Ukrainian spring.

Like pro-Russian rebels, Ukrainian soldiers rarely provide their real names when talking to journalists, using platoon nicknames instead.

We want to build a new independent and sovereign Ukraine. That's what makes us different from other military units.

The 22-year-old, 6-foot 2-inch bearded soldier showing me around is called Dancer.

A roads engineer graduate from Luhansk, Dancer joined the Azov battalion last year shortly after the armed conflict began in eastern Ukraine, attracted by the militia group's long-term goals.

"Our battalion is comprised of conscious people who have a much higher purpose than just winning the war," he said.

"We want to build a new independent and sovereign Ukraine. That's what makes us different from other military units."

The Azov battalion is a volunteer military brigade that was formed last year in Mariupol, named after the sea on which the city is located.

It is closely linked to the Social-National Assembly, an umbrella organisation to a collection of ultra-nationalist and neo-Nazi groups in Ukraine, and many of Azov's recruits are drawn by its perceived far right-wing ideology.

Currently under the auspices of Ukraine's interior ministry, there are deep concerns that arming right-wing paramilitary groups like Azov might backfire and present a future threat to the government, but Dancer says the fears are unfounded.

"The battalion operates as a professional military unit," he said.

"The commanders listen to you while you listen to your subordinates, and all the daily and military questions are solved in a democratic way.

"There is no violence against younger conscripts in Azov, no stupid orders and notations."

Azov volunteers fight alongside regular Ukrainian forces and were amongst the earliest to see action in the conflict last year and its troops have a fearless reputation.

"I wanted to join a battalion that would be on the frontline and participate in real action," Dancer said...

By Nicholas Lazaredes in Ukraine

Posted Thu 12 Mar 2015 at 7:24pm Thursday 12 Mar 2015 at 7:24pm, updated Tue 24 Mar 2015 at 6:30am

Awe, crud-buns! That was under OBama's watch. Go figure!?!

But I'm confident they are still a swell bunch-o-fellas.

- Why_Yes_I_Do

- 03-28-2022, 02:23 PM

- LexusLover

- 03-28-2022, 02:32 PM

Is someone advocating challenging a lunatic fighting for his own life?

The Box: John Denver

The Box: John Denver

Once upon a time in the land of hushabye

In the woundrous days of yore

They came upon this kind of box

All bound with chains and locked with locks

And labelled "kindly do not Touch, it's WAR"

Decree was issued round about

All with a flourish and a shout

And gayley colored mascots trippling lightly on the fore

"Do not tamper with this deadly box"

"Don"t break the chains or pick the locks"

"Please don't ever play about with war"

Well the children understood

Children happen to be good

And they were just as around the time of yore

They didn't try to break the chains or pick the locks

They didn't play about with war

Mommies didn't either

Sisters aunts grannies neither

They were quiet and sweet and pretty in those wondrous days of yore

Fairley much the same as now

Not the ones to blame somehow

For opning up that deadly box of war.

But someone did,

Someone battered in the lid

And spilled the insides out across the floor

A Kind of bouncy bumpy ball, filled with guns and flags and all the tears and

Horror and death, that goes with war.

It bounced right out and went crashing all about

And bumping into everything in store

And what was sad and most unfair

Is that it didn't really seem to care much who it bumped

Or why, or what, or for.

It bumped the children mainly

And I'll tell you this quite plainly

It bumps them evry day and more, and more

And leaves them dead and burned and dying

Thousands of them sick and crying

Cos when it bumps

Its really very sore

Now theres a way to stop the ball

It isn't difficult at all

All it takes is wisdom

And I'm absolutley sure

We can get the ball back in the box

And bind the chains

And lock the locks

No one seems to want to save the children any more

Well thats the way it all appears

That balls been bouncing round for years and years

In spite of all the wisdom whiz since those wondrous days of yore

When they came upon this kind of box

All bound with chains and locked with locks

And labelled "Kindly do not touch"

"ITS WAR"

- dilbert firestorm

- 03-28-2022, 10:06 PM

https://www.realcleardefense.com/art...od_823985.html

The Marines Got Rid of Their Tanks. Is Ukraine Making Them Look Smart, or Too Smart for Their Own Good?

.

By Ben Connable March 28, 2022

Anyone watching video footage of the war in Ukraine has seen Ukrainian light infantry destroying lots of Russian tanks. In one video, a British NLAW—a cheap, single-shot, shoulder-launched rocket—darts out over the top of a tank, blasts a hole in its thin top armor, and sets it on fire. In another video, a Ukrainian drone follows a hapless Russian tank down a street before it, too, is destroyed by rockets, setting it on fire and sending a lone surviving crewman scrambling for cover. Video after video, photo after photo, shows almost every variant of Russian tank lying tracked and crippled on a highway, smoldering in a field of burnt grass, or decapitated, cast metal gun turret lying uselessly in the mud a few feet from its body.

Poor tank performance in Ukraine does not bode well for the armor-dependent Russians. It also may not bode well for the future of the tank as a tool of modern warfare. Marine Commandant David H. Berger sees the Ukraine war as vindication of his Force Design 2030. Last year, the Marine Corps got rid of the last of its active duty tank units and most of its traditional tube artillery as part of FD2030. This was Berger’s plan to reshape the Marine Corps primarily to fight a prospective long-range, high-tech, over-water war with China. Berger has taken—and is taking—plenty of barbs from within the senior ranks of the Marine Corps and from external critics for his new direction. Given what has happened to tanks in Ukraine, was Berger prescient?

Maybe. He published his force design plan in March 2020. In it, he wrote on the divestiture of tanks, “We have sufficient evidence to conclude that this capability, despite its long and honorable history in the wars of the past, is operationally unsuitable for our highest-priority challenges in the future.” Two important points leap out from FD2030, particularly from this quoted paragraph.

First, Berger is betting big on the China fight because he believes he has to. Defense officials told the Marines to focus on China as a pacing threat, a threat that should guide the service’s man, train, and equip mission. If the Marine Corps has to man, train, and equip to fight China, then tanks, cannons, and infantry may have less value. Even a glance at the map of the vast expanse of the Western Pacific Ocean lends weight to the argument that tanks have no place in the counter-China fight. War in the South China Sea is envisioned as a long-range battle fought between networks of sensors and missiles mounted on warships, fifth-generation combat aircraft, and satellites. Tanks deployed to remote islands might be little more than fuel-sucking targets for Chinese missiles.

Second, contrary to the suggestions of his critics, in FD2030, Berger did not explicitly argue that tanks are valueless in modern warfare. Instead, he appeared to be arguing that because tanks are useless in the Western Pacific theater, the Corps had to divest its armor and invest in technology appropriate for the “highest-priority” China fight. He made clear the U.S. Army would continue to provide “heavy ground armor capability” for what he insinuates are lower-priority fights in places like the Middle East, the Korean Peninsula, and Europe (that insinuation requires a separate article).

Within the narrow scope of Berger’s argument, he appears to be right. Tanks probably are useless in the counter-China fight in the Western Pacific theater. But Berger’s apparently dogmatic pursuit of the pacing threat raises some valid critiques. Have Department of Defense officials really forced the Marine Corps to focus so intensively on a single prospective enemy in one imagined battle in one geographic area, or is Berger embracing these directions more fervently than is required? Is Berger betting on the hope that Marines will never again have to help the Army fight a conventional ground war as they did in World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War, and the Iraq invasion? Is he cutting tanks and artillery and some infantry with an explicit intent to keep the Marines out of conventional wars?

It seems more likely he’s making an even bigger bet: That the redesign for the China fight will create a fungible lightweight, high-tech capability allowing the Marines to help the joint force in any operation. In this view, war itself has changed. Precision missiles, drones, cyber capabilities, and fast, light vehicles are the right fit for China, and also Iran, North Korea, Russia, the Islamic State, and any other prospective adversary.

In that case, FD2030 may not just be a redesign for the China fight, it may be the 1990s Revolution in Military Affairs reborn. Going forward, Berger may see Marines serving as (in the language of the RMA) high-tech gears in a global, joint, network-centric, effects-based sensor-shooter network that will be able to see and kill anything of military value, anywhere. Tanks have no place in this vision. Therefore, as Berger let on in his recent remarks on events in Ukraine, he may indeed believe that tanks are universally impractical even beyond the China fight.

If Berger is making this big revolutionary bet, then he’s under even more pressure to be right. Innovation like the kind he is trying to enact requires forecasting the character of war in the near future. Forecasting requires imagining the future and also describing the present as a rational, evidence-driven point of departure. Recently, Berger asked for more critique of his forecast and plan. Here’s mine: If he wants the Marines and his critics to embrace his divestiture of tanks (and most cannon artillery) then he needs to do a better job anchoring his imaginative vision in evidence from recent, demonstrated performance.

There is plenty of evidence to examine. Conventional warfare is commonplace around the world. Just in the past fifteen years, tanks, artillery, infantry, drones, and precision munitions have been used, or are still used routinely in Syria, Libya, Armenia-Azerbaijan, Ethiopia-Tigray, Afghanistan, Yemen, Chad, Pakistan, Gaza, Mali, Georgia, Lebanon, and Ukraine. Some trends and caveats appear in a cursory examination.

In many cases, tanks appear to be particularly vulnerable to drones synchronized with precision munitions. Drones can loiter overhead, pinpoint their targets, and either launch their own precision munitions onto the tanks’ soft top armor or guide in other munitions. Ukrainians have used this drone-missile combination with deadly effect. Turkish Bayraktar TB2 and Chinese Wing Loong II drones have been particularly successful against tanks in Ukraine and in Armenia and Ethiopia. Tigrayan officers report a sense of helplessness as perhaps ten drones overflew their positions, killing tanks, troops, and other vehicles at will.

On the ground in most of these conflicts, light infantry, and even novice militiamen have used antitank missiles and direct-fire, short-range antitank rockets to wreak havoc on tanks and on their accompanying lighter armored vehicles. Ukraine has been a showcase for the U.S.-made Javelin antitank missile, a fire-and-forget top attack weapon used to great effect by Marines against Taliban positions in Afghanistan. In a March 16th interview, Berger stated that “it was pretty clear that top-down sort of missile attacks on the top side of heavy armor, makes it pretty vulnerable.” Even direct-fire antitank rockets manufactured by the Americans, Germans, and others, have been used to knock out hundreds of tanks. It seems that tanks—the original purveyors of shock and awe on the battlefield—are now prey.

However, there are some other commonalities to these battles that might undermine the conclusion that tanks have been made anachronistic. Both technical and tactical factors contributed to these outcomes. First, it is important to note that the top-down missile attack capability Berger cites as evidence for the obsolescence of tanks is at least forty years old. Sweden’s Bofors Infantry, Light and Lethal (BILL) missile was designed in the late 1970s and adopted by the Swedes in 1988, three years before Operation Desert Storm. It is true that top-attack missiles and rockets did not widely proliferate until the last two decades, but they are nothing new.

In all of the most recent cases of conventional warfare—Armenia, Tigray, Ukraine, Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Ukraine—the tanks being destroyed are almost entirely older model Russian tanks like the T-62, T-72, and T-80. Some have been upgraded with bolt-on anti-rocket side armor but not with extensive top armor. Few appear to have been fitted with functioning active protection, anti-warhead kits like the U.S. Army’s Trophy system. Some passive protection kits on even the leading Russian tank units in Ukraine appear to have been in disrepair, leaving tanks vulnerable to light shoulder-fired rockets. Russia’s new Armata T-14 tank with its Trophy-like active defense system has not yet made a public appearance in Ukraine, so it is not possible to tell if it would change the battlefield calculus.

Drones have played a key role in most of these conflicts. Anywhere drones fly, missiles, rockets, or artillery shells often follow. Tanks commonly are victims. Some drone attacks are elegant in their simplicity. For example, in this video, a drone is used to help a Ukrainian infantryman with a direct-fire rocket take out a Russian truck.

But drones are also lumbering, loud, and usually highly visible even to the naked eye. Bayraktars may be wreaking havoc in Ukraine, but they reportedly are being decimated by Russian air defense systems in Libya and Syria. Smaller commercial drones have also been effective, but these, too, are vulnerable to anti-drone fires. Azerbaijani and Ethiopian successes with drones may not tell a convincing story. The Azeris effectively stripped away Armenian air defenses to give its drones free rein, bringing into question the value of drones in relation to a basic propeller-driven aircraft that might carry five to ten times as many munitions. The Tigrayans had few and mostly antiquated air defenses, so once these were stripped away they, too, were vulnerable to all types of air attack. In Ukraine, the Russians are failing to protect their Pantsir S1 missile and gun systems that would normally be used to kill drones. None of these cases undermine the extant planning assumption that good short-range air defenses kill drones, attack aircraft, helicopters, giving tanks, artillery, and infantry more survivability and freedom of movement.

Logistics, will to fight, and tactics also shape the efficacy of tanks in combat. Tanks are tools. When they are properly cared for and applied for their intended uses, they are generally more effective than when they are neglected or overused. At least in Ukraine, bad Russian logistics, willpower, tactics, and battlefield practices appear to have sharply exacerbated their tanks’ vulnerabilities. Russian tankers are abandoning some tanks because they have no fuel. This is a failure of supply, not of the tank. Some Russians appear to be abandoning their tanks out of fear. Based on public videos, interviews, and reports, it appears the Russians are repeatedly driving their tanks buttoned up (with crew peering through narrow vision slits or scopes) on main roads in broad daylight without flanking air reconnaissance, anti-air defenses, or dismounted infantry support. Some tanks have been recorded fighting solo in dense urban terrain. Russians appear to have no interest in using camouflage, smoke, dispersal, radio discipline, or any of the other basic practices necessary for battlefield survival. To experienced warfighters, the Russians appear to be bizarrely pursuing self-destruction. It is not yet clear if Ukraine is more a case of poor tank performance or poor Russian performance.

From an analytic standpoint, I am most concerned with the lack of evidentiary balance coming in from the Ukraine war. It is possible to access reams of evidence showing tanks’ vulnerabilities, and very hard to find any evidence that tanks have done anything useful beyond shelling apartment buildings. Is that it? Have no Russian tanks blown up any Ukrainian military vehicles from maximum range, or killed Ukrainian infantry with their mounted machineguns? Ukrainian video evidence is also generally bereft of their own tank actions. There is another side to this story.

So when it comes to the tank argument, the evidence has to be described as inconclusive. One could examine these few cases and find plenty of evidence to support the FD2030 vision, and plenty to tear it apart. The cannon artillery argument might be even more complex.

On the surface of these cases, and others, missiles and rockets appear to be the dominant form of fires in modern warfare. But old-school tube artillery is far more prolific in all conflicts, including in Ukraine. It has played an important but relatively unsung role even in the counter-Islamic State fight in Syria and Iraq, where advanced precision munitions have garnered the most attention. For example, one Marine artillery battalion alone fired 35,000 artillery rounds in and around Raqqa, Syria, over five months of fighting, outstripping the total number of rounds fired during the entire invasion of Iraq in 2003. During the invasion of southern Lebanon in 2006, Israeli cannoneers reportedly fired 170,000 artillery rounds, nearly three times as many as were fired in all of Operations Desert Shield and Storm. Clearly, cannon artillery is still in prolific use. But there does not appear to be a strong, detailed, transparent, evidence-driven argument that it is or is not both useful and necessary.

It is also possible that the tank and artillery debates are obscuring an even more relevant issue for the future of the Marine Corps. The Corps has always been an infantry-centric organization. Berger cut some infantry units and reshaped others to make them lighter and more high-tech. Is he on the right track? In Ukraine, we are seeing infantry ambush and kill tanks, conduct battalion-level combined-arms assaults, defend urban areas, and execute squad- and platoon-sized raids. Light Ukrainian infantry appear to be excelling, while heavy Russian infantry are having mixed success. One could argue that basic infantry are dominating the fight in Ukraine, or that traditional infantry formations have been ineffective, or some combination thereof. So, what does Ukraine, and all of these cases of modern conventional war tell us about the value of basic infantry, the kind that suffered modest cuts in FD2030? This question, too, remains unanswered.

For now, it is not clear if the Marine Corps is going in an objectively better direction than it was before Berger took office. Neither the Commandant nor his critics have done a good enough job laying out all of the evidence and analyses in support of their arguments. Berger’s critics should work diligently to ensure they are not relying too heavily upon their dated personal experiences and well-entrenched opinions. But the real burden falls on Berger. This is not his Marine Corps. It belongs to all Americans, and this is our collective national security he is betting with. The tanks and most of the artillery are gone, but they can be brought back. Rebuilding infantry battalions is trickier. Berger should make a stronger, more transparent argument to help the next commandant guide the Corps’ future.

The Marines Got Rid of Their Tanks. Is Ukraine Making Them Look Smart, or Too Smart for Their Own Good?

.

By Ben Connable March 28, 2022

Anyone watching video footage of the war in Ukraine has seen Ukrainian light infantry destroying lots of Russian tanks. In one video, a British NLAW—a cheap, single-shot, shoulder-launched rocket—darts out over the top of a tank, blasts a hole in its thin top armor, and sets it on fire. In another video, a Ukrainian drone follows a hapless Russian tank down a street before it, too, is destroyed by rockets, setting it on fire and sending a lone surviving crewman scrambling for cover. Video after video, photo after photo, shows almost every variant of Russian tank lying tracked and crippled on a highway, smoldering in a field of burnt grass, or decapitated, cast metal gun turret lying uselessly in the mud a few feet from its body.

Poor tank performance in Ukraine does not bode well for the armor-dependent Russians. It also may not bode well for the future of the tank as a tool of modern warfare. Marine Commandant David H. Berger sees the Ukraine war as vindication of his Force Design 2030. Last year, the Marine Corps got rid of the last of its active duty tank units and most of its traditional tube artillery as part of FD2030. This was Berger’s plan to reshape the Marine Corps primarily to fight a prospective long-range, high-tech, over-water war with China. Berger has taken—and is taking—plenty of barbs from within the senior ranks of the Marine Corps and from external critics for his new direction. Given what has happened to tanks in Ukraine, was Berger prescient?

Maybe. He published his force design plan in March 2020. In it, he wrote on the divestiture of tanks, “We have sufficient evidence to conclude that this capability, despite its long and honorable history in the wars of the past, is operationally unsuitable for our highest-priority challenges in the future.” Two important points leap out from FD2030, particularly from this quoted paragraph.

First, Berger is betting big on the China fight because he believes he has to. Defense officials told the Marines to focus on China as a pacing threat, a threat that should guide the service’s man, train, and equip mission. If the Marine Corps has to man, train, and equip to fight China, then tanks, cannons, and infantry may have less value. Even a glance at the map of the vast expanse of the Western Pacific Ocean lends weight to the argument that tanks have no place in the counter-China fight. War in the South China Sea is envisioned as a long-range battle fought between networks of sensors and missiles mounted on warships, fifth-generation combat aircraft, and satellites. Tanks deployed to remote islands might be little more than fuel-sucking targets for Chinese missiles.

Second, contrary to the suggestions of his critics, in FD2030, Berger did not explicitly argue that tanks are valueless in modern warfare. Instead, he appeared to be arguing that because tanks are useless in the Western Pacific theater, the Corps had to divest its armor and invest in technology appropriate for the “highest-priority” China fight. He made clear the U.S. Army would continue to provide “heavy ground armor capability” for what he insinuates are lower-priority fights in places like the Middle East, the Korean Peninsula, and Europe (that insinuation requires a separate article).

Within the narrow scope of Berger’s argument, he appears to be right. Tanks probably are useless in the counter-China fight in the Western Pacific theater. But Berger’s apparently dogmatic pursuit of the pacing threat raises some valid critiques. Have Department of Defense officials really forced the Marine Corps to focus so intensively on a single prospective enemy in one imagined battle in one geographic area, or is Berger embracing these directions more fervently than is required? Is Berger betting on the hope that Marines will never again have to help the Army fight a conventional ground war as they did in World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War, and the Iraq invasion? Is he cutting tanks and artillery and some infantry with an explicit intent to keep the Marines out of conventional wars?

It seems more likely he’s making an even bigger bet: That the redesign for the China fight will create a fungible lightweight, high-tech capability allowing the Marines to help the joint force in any operation. In this view, war itself has changed. Precision missiles, drones, cyber capabilities, and fast, light vehicles are the right fit for China, and also Iran, North Korea, Russia, the Islamic State, and any other prospective adversary.

In that case, FD2030 may not just be a redesign for the China fight, it may be the 1990s Revolution in Military Affairs reborn. Going forward, Berger may see Marines serving as (in the language of the RMA) high-tech gears in a global, joint, network-centric, effects-based sensor-shooter network that will be able to see and kill anything of military value, anywhere. Tanks have no place in this vision. Therefore, as Berger let on in his recent remarks on events in Ukraine, he may indeed believe that tanks are universally impractical even beyond the China fight.

If Berger is making this big revolutionary bet, then he’s under even more pressure to be right. Innovation like the kind he is trying to enact requires forecasting the character of war in the near future. Forecasting requires imagining the future and also describing the present as a rational, evidence-driven point of departure. Recently, Berger asked for more critique of his forecast and plan. Here’s mine: If he wants the Marines and his critics to embrace his divestiture of tanks (and most cannon artillery) then he needs to do a better job anchoring his imaginative vision in evidence from recent, demonstrated performance.

There is plenty of evidence to examine. Conventional warfare is commonplace around the world. Just in the past fifteen years, tanks, artillery, infantry, drones, and precision munitions have been used, or are still used routinely in Syria, Libya, Armenia-Azerbaijan, Ethiopia-Tigray, Afghanistan, Yemen, Chad, Pakistan, Gaza, Mali, Georgia, Lebanon, and Ukraine. Some trends and caveats appear in a cursory examination.

In many cases, tanks appear to be particularly vulnerable to drones synchronized with precision munitions. Drones can loiter overhead, pinpoint their targets, and either launch their own precision munitions onto the tanks’ soft top armor or guide in other munitions. Ukrainians have used this drone-missile combination with deadly effect. Turkish Bayraktar TB2 and Chinese Wing Loong II drones have been particularly successful against tanks in Ukraine and in Armenia and Ethiopia. Tigrayan officers report a sense of helplessness as perhaps ten drones overflew their positions, killing tanks, troops, and other vehicles at will.

On the ground in most of these conflicts, light infantry, and even novice militiamen have used antitank missiles and direct-fire, short-range antitank rockets to wreak havoc on tanks and on their accompanying lighter armored vehicles. Ukraine has been a showcase for the U.S.-made Javelin antitank missile, a fire-and-forget top attack weapon used to great effect by Marines against Taliban positions in Afghanistan. In a March 16th interview, Berger stated that “it was pretty clear that top-down sort of missile attacks on the top side of heavy armor, makes it pretty vulnerable.” Even direct-fire antitank rockets manufactured by the Americans, Germans, and others, have been used to knock out hundreds of tanks. It seems that tanks—the original purveyors of shock and awe on the battlefield—are now prey.

However, there are some other commonalities to these battles that might undermine the conclusion that tanks have been made anachronistic. Both technical and tactical factors contributed to these outcomes. First, it is important to note that the top-down missile attack capability Berger cites as evidence for the obsolescence of tanks is at least forty years old. Sweden’s Bofors Infantry, Light and Lethal (BILL) missile was designed in the late 1970s and adopted by the Swedes in 1988, three years before Operation Desert Storm. It is true that top-attack missiles and rockets did not widely proliferate until the last two decades, but they are nothing new.

In all of the most recent cases of conventional warfare—Armenia, Tigray, Ukraine, Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Ukraine—the tanks being destroyed are almost entirely older model Russian tanks like the T-62, T-72, and T-80. Some have been upgraded with bolt-on anti-rocket side armor but not with extensive top armor. Few appear to have been fitted with functioning active protection, anti-warhead kits like the U.S. Army’s Trophy system. Some passive protection kits on even the leading Russian tank units in Ukraine appear to have been in disrepair, leaving tanks vulnerable to light shoulder-fired rockets. Russia’s new Armata T-14 tank with its Trophy-like active defense system has not yet made a public appearance in Ukraine, so it is not possible to tell if it would change the battlefield calculus.

Drones have played a key role in most of these conflicts. Anywhere drones fly, missiles, rockets, or artillery shells often follow. Tanks commonly are victims. Some drone attacks are elegant in their simplicity. For example, in this video, a drone is used to help a Ukrainian infantryman with a direct-fire rocket take out a Russian truck.

But drones are also lumbering, loud, and usually highly visible even to the naked eye. Bayraktars may be wreaking havoc in Ukraine, but they reportedly are being decimated by Russian air defense systems in Libya and Syria. Smaller commercial drones have also been effective, but these, too, are vulnerable to anti-drone fires. Azerbaijani and Ethiopian successes with drones may not tell a convincing story. The Azeris effectively stripped away Armenian air defenses to give its drones free rein, bringing into question the value of drones in relation to a basic propeller-driven aircraft that might carry five to ten times as many munitions. The Tigrayans had few and mostly antiquated air defenses, so once these were stripped away they, too, were vulnerable to all types of air attack. In Ukraine, the Russians are failing to protect their Pantsir S1 missile and gun systems that would normally be used to kill drones. None of these cases undermine the extant planning assumption that good short-range air defenses kill drones, attack aircraft, helicopters, giving tanks, artillery, and infantry more survivability and freedom of movement.

Logistics, will to fight, and tactics also shape the efficacy of tanks in combat. Tanks are tools. When they are properly cared for and applied for their intended uses, they are generally more effective than when they are neglected or overused. At least in Ukraine, bad Russian logistics, willpower, tactics, and battlefield practices appear to have sharply exacerbated their tanks’ vulnerabilities. Russian tankers are abandoning some tanks because they have no fuel. This is a failure of supply, not of the tank. Some Russians appear to be abandoning their tanks out of fear. Based on public videos, interviews, and reports, it appears the Russians are repeatedly driving their tanks buttoned up (with crew peering through narrow vision slits or scopes) on main roads in broad daylight without flanking air reconnaissance, anti-air defenses, or dismounted infantry support. Some tanks have been recorded fighting solo in dense urban terrain. Russians appear to have no interest in using camouflage, smoke, dispersal, radio discipline, or any of the other basic practices necessary for battlefield survival. To experienced warfighters, the Russians appear to be bizarrely pursuing self-destruction. It is not yet clear if Ukraine is more a case of poor tank performance or poor Russian performance.

From an analytic standpoint, I am most concerned with the lack of evidentiary balance coming in from the Ukraine war. It is possible to access reams of evidence showing tanks’ vulnerabilities, and very hard to find any evidence that tanks have done anything useful beyond shelling apartment buildings. Is that it? Have no Russian tanks blown up any Ukrainian military vehicles from maximum range, or killed Ukrainian infantry with their mounted machineguns? Ukrainian video evidence is also generally bereft of their own tank actions. There is another side to this story.

So when it comes to the tank argument, the evidence has to be described as inconclusive. One could examine these few cases and find plenty of evidence to support the FD2030 vision, and plenty to tear it apart. The cannon artillery argument might be even more complex.

On the surface of these cases, and others, missiles and rockets appear to be the dominant form of fires in modern warfare. But old-school tube artillery is far more prolific in all conflicts, including in Ukraine. It has played an important but relatively unsung role even in the counter-Islamic State fight in Syria and Iraq, where advanced precision munitions have garnered the most attention. For example, one Marine artillery battalion alone fired 35,000 artillery rounds in and around Raqqa, Syria, over five months of fighting, outstripping the total number of rounds fired during the entire invasion of Iraq in 2003. During the invasion of southern Lebanon in 2006, Israeli cannoneers reportedly fired 170,000 artillery rounds, nearly three times as many as were fired in all of Operations Desert Shield and Storm. Clearly, cannon artillery is still in prolific use. But there does not appear to be a strong, detailed, transparent, evidence-driven argument that it is or is not both useful and necessary.

It is also possible that the tank and artillery debates are obscuring an even more relevant issue for the future of the Marine Corps. The Corps has always been an infantry-centric organization. Berger cut some infantry units and reshaped others to make them lighter and more high-tech. Is he on the right track? In Ukraine, we are seeing infantry ambush and kill tanks, conduct battalion-level combined-arms assaults, defend urban areas, and execute squad- and platoon-sized raids. Light Ukrainian infantry appear to be excelling, while heavy Russian infantry are having mixed success. One could argue that basic infantry are dominating the fight in Ukraine, or that traditional infantry formations have been ineffective, or some combination thereof. So, what does Ukraine, and all of these cases of modern conventional war tell us about the value of basic infantry, the kind that suffered modest cuts in FD2030? This question, too, remains unanswered.

For now, it is not clear if the Marine Corps is going in an objectively better direction than it was before Berger took office. Neither the Commandant nor his critics have done a good enough job laying out all of the evidence and analyses in support of their arguments. Berger’s critics should work diligently to ensure they are not relying too heavily upon their dated personal experiences and well-entrenched opinions. But the real burden falls on Berger. This is not his Marine Corps. It belongs to all Americans, and this is our collective national security he is betting with. The tanks and most of the artillery are gone, but they can be brought back. Rebuilding infantry battalions is trickier. Berger should make a stronger, more transparent argument to help the next commandant guide the Corps’ future.