Trump gave a rather divisive speech in South Dakota on Friday. Very little I would consider "uplifting" about it. He did complain quite a bit but I do agree with his words. I couldn't tell you what he did on Saturday.Divisive? I guess you’re in favor of destroying Mt Rushmore? Defunding or eliminating LE? No Speedy, Trump wasn’t being divisive. He was talking about the rule of law, protecting historic monuments. Meanwhile the carnage in the cities is getting worse. Infants and teenagers are getting shot in cold blood in the streets. Where’s Biden? He doesn’t speak out because defunding the police and destroying our history is the Democratic platform.

As for Biden:

Biden and Trump Deliver Very Different Messages on July 4th

Former Vice President Joe Biden offered a message of hope and unity on Fourth of July that was in sharp contrast to the divisive tone of President Donald Trump’s address at Mount Rushmore on Friday. With a message that centered around racial justice, Biden said that the United States “never lived up” to its founding principle that “all men are created equal.” In a video that includes images of protests and references to the Black Lives Matter movement, Biden offered a hopeful tone, saying that “We have a chance to rip the roots of systemic racism out of this country” and “live up to the words that founded this nation.” Trump on the other hand delivered a “dark speech” that amounted to “a full-on culture war against a straw-man version of the left that he portrayed as inciting mayhem and moving the country toward totalitarianism,” as the New York Times puts it.

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/...-rushmore.html Originally Posted by SpeedRacerXXX

- bambino

- 07-06-2020, 08:15 AM

- oeb11

- 07-06-2020, 09:25 AM

b-agreed - The LSM completely mis-characterized the speech - their usual propaganda Lies.

i agree with You.

i agree with You.

- rexdutchman

- 07-06-2020, 09:35 AM

Joey hiddin in the basement An yes agree LSM propaganda and lies

- bambino

- 07-06-2020, 10:05 AM

- gfejunkie

- 07-06-2020, 10:07 AM

- rexdutchman

- 07-06-2020, 10:25 AM

The NYT WP cnn etc really thing if your OPINION is different you need to be locked up ( re - ed camps)

- LexusLover

- 07-06-2020, 10:53 AM

- gnadfly

- 07-06-2020, 11:59 AM

Biden thought it was July 4, 1944. Didn't go anywhere because he couldn't find his gas rationing coupons.

- SpeedRacerXXX

- 07-07-2020, 07:49 AM

Divisive? I guess you’re in favor of destroying Mt Rushmore? Defunding or eliminating LE? No Speedy, Trump wasn’t being divisive. He was talking about the rule of law, protecting historic monuments. Meanwhile the carnage in the cities is getting worse. Infants and teenagers are getting shot in cold blood in the streets. Where’s Biden? He doesn’t speak out because defunding the police and destroying our history is the Democratic platform. Originally Posted by bambinoNo I'm not in favor of doing anything to Mt. Rushmore. Did you read the link I cited? THe July 4th holiday is one that is supposed to be uplifting, love for our country. Trump turned the speech into a negative with comments such as this:

The violent mayhem we have seen in the streets of cities that are run by liberal Democrats, in every case, is the predictable result of years of extreme indoctrination and bias in education, journalism, and other cultural institutions.

Against every law of society and nature, our children are taught in school to hate their own country, and to believe that the men and women who built it were not heroes, but that were villains. The radical view of American history is a web of lies — all perspective is removed, every virtue is obscured, every motive is twisted, every fact is distorted, and every flaw is magnified until the history is purged and the record is disfigured beyond all recognition.

So much BS.

Again, Trump's comments did nothing to attract undecided voters to support him. He once again pandered to his base.

- SpeedRacerXXX

- 07-07-2020, 07:52 AM

We obviously heard a different speech. Was the one you heard in English?Lying again???

When you threatened to kick my ass all the way back from Austin ... was that "divisive"? Originally Posted by LexusLover

I never threatened to kick your ass. I said I was capable of kicking your ass. A statement I still stand behind.

- SpeedRacerXXX

- 07-07-2020, 07:54 AM

Biden thought it was July 4, 1944. Didn't go anywhere because he couldn't find his gas rationing coupons. Originally Posted by gnadflyAnd yet Biden leads Trump in every poll, whether it be approval ratings, preference at the national level, or polls within the battleground states.

What does that say about Trump?

- oeb11

- 07-07-2020, 09:24 AM

No I'm not in favor of doing anything to Mt. Rushmore. Did you read the link I cited? THe July 4th holiday is one that is supposed to be uplifting, love for our country. Trump turned the speech into a negative with comments such as this:

The violent mayhem we have seen in the streets of cities that are run by liberal Democrats, in every case, is the predictable result of years of extreme indoctrination and bias in education, journalism, and other cultural institutions.

Against every law of society and nature, our children are taught in school to hate their own country, and to believe that the men and women who built it were not heroes, but that were villains. The radical view of American history is a web of lies — all perspective is removed, every virtue is obscured, every motive is twisted, every fact is distorted, and every flaw is magnified until the history is purged and the record is disfigured beyond all recognition.

So much BS.

Again, Trump's comments did nothing to attract undecided voters to support him. He once again pandered to his base. Originally Posted by SpeedRacerXXX

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/ar...roject/604093/

Ideas

The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts

A dispute between a small group of scholars and the authors of The New York Times Magazine’s issue on slavery represents a fundamental disagreement over the trajectory of American society.

December 23, 2019 <img class="c-article-author__img o-media__img lazyloaded" data-srcset="https://cdn.theatlantic.com/thumbor/iH-ujYm6NpXOm40FRPGGeqACqQ8=/343x0:1710x1365/200x200/media/None/FullSizeRender-4/original.jpg, https://cdn.theatlantic.com/thumbor/...4/original.jpg 2x" alt="">

Adam Serwer

Staff writer at The Atlantic

Enjoy unlimited access to The Atlantic for less than $1 per week.

Sign in Subscribe Now

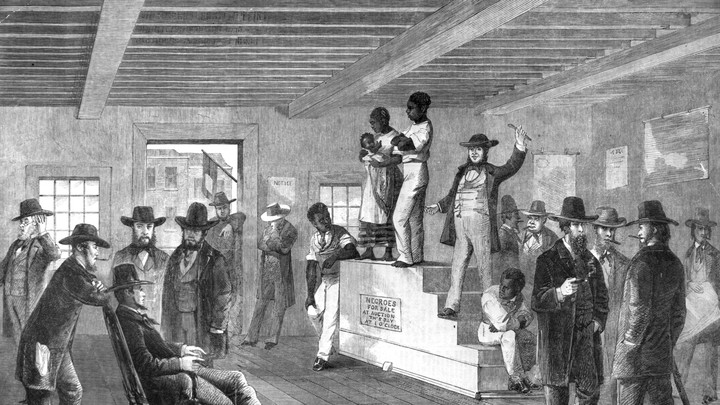

Bettmann / Getty

Bettmann / Getty

When The New York Times Magazine published its 1619 Project in August, people lined up on the street in New York City to get copies. Since then, the project—a historical analysis of how slavery shaped American political, social, and economic institutions—has spawned a podcast, a high-school curriculum, and an upcoming book. For Nikole Hannah-Jones, the reporter who conceived of the project, the response has been deeply gratifying.

Make your inbox more interesting

Each weekday evening, get an overview of the day’s biggest news, along with fascinating ideas, images, and voices.

Email Address (required)

Each weekday evening, get an overview of the day’s biggest news, along with fascinating ideas, images, and voices.

Email Address (required)

Thanks for signing up!

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

“They had not seen this type of demand for a print product of The New York Times, they said, since 2008, when people wanted copies of Obama's historic presidency edition,” Hannah-Jones told me. “I know when I talk to people, they have said that they feel like they are understanding the architecture of their country in a way that they had not.”

U.S. history is often taught and popularly understood through the eyes of its great men, who are seen as either heroic or tragic figures in a global struggle for human freedom. The 1619 Project, named for the date of the first arrival of Africans on American soil, sought to place “the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” Viewed from the perspective of those historically denied the rights enumerated in America’s founding documents, the story of the country’s great men necessarily looks very different.

More by this writer

-

Julián Castro: ‘This Is the Time to Make Change’

Adam Serwer -

Trump Is Struggling to Run Against a White Guy

Adam Serwer -

Roberts Wanted Minimal Competence, but Trump Couldn’t Deliver

Adam Serwer

The reaction to the project was not universally enthusiastic. Several weeks ago, the Princeton historian Sean Wilentz, who had criticized the 1619 Project’s “cynicism” in a lecture in November, began quietly circulating a letter objecting to the project, and some of Hannah-Jones’s work in particular. The letter acquired four signatories—James McPherson, Gordon Wood, Victoria Bynum, and James Oakes, all leading scholars in their field. They sent their letter to three top Times editors and the publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, on December 4. A version of that letter was published on Friday, along with a detailed rebuttal from Jake Silverstein, the editor of the Times Magazine.

The letter sent to the Times says, “We applaud all efforts to address the foundational centrality of slavery and racism to our history,” but then veers into harsh criticism of the 1619 Project. The letter refers to “matters of verifiable fact” that “cannot be described as interpretation or ‘framing’” and says the project reflected “a displacement of historical understanding by ideology.” Wilentz and his fellow signatories didn’t just dispute the Times Magazine’s interpretation of past events, but demanded corrections.

In the age of social-media invective, a strongly worded letter might not seem particularly significant. But given the stature of the historians involved, the letter is a serious challenge to the credibility of the 1619 Project, which has drawn its share not just of admirers but also critics.

Nevertheless, some historians who declined to sign the letter wondered whether the letter was intended less to resolve factual disputes than to discredit laymen who had challenged an interpretation of American national identity that is cherished by liberals and conservatives alike.

“I think had any of the scholars who signed the letter contacted me or contacted the Times with concerns [before sending the letter], we would've taken those concerns very seriously,” Hannah-Jones said. “And instead there was kind of a campaign to kind of get people to sign on to a letter that was attempting really to discredit the entire project without having had a conversation.”

Underlying each of the disagreements in the letter is not just a matter of historical fact but a conflict about whether Americans, from the Founders to the present day, are committed to the ideals they claim to revere. And while some of the critiques can be answered with historical fact, others are questions of interpretation grounded in perspective and experience.

In fact, the harshness of the Wilentz letter may obscure the extent to which its authors and the creators of the 1619 Project share a broad historical vision. Both sides agree, as many of the project’s right-wing critics do not, that slavery’s legacy still shapes American life—an argument that is less radical than it may appear at first glance. If you think anti-black racism still shapes American society, then you are in agreement with the thrust of the 1619 Project, though not necessarily with all of its individual arguments.

The clash between the Times authors and their historian critics represents a fundamental disagreement over the trajectory of American society. Was America founded as a slavocracy, and are current racial inequities the natural outgrowth of that? Or was America conceived in liberty, a nation haltingly redeeming itself through its founding principles? These are not simple questions to answer, because the nation’s pro-slavery and anti-slavery tendencies are so closely intertwined.

The letter is rooted in a vision of American history as a slow, uncertain march toward a more perfect union. The 1619 Project, and Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay in particular, offer a darker vision of the nation, in which Americans have made less progress than they think, and in which black people continue to struggle indefinitely for rights they may never fully realize. Inherent in that vision is a kind of pessimism, not about black struggle but about the sincerity and viability of white anti-racism. It is a harsh verdict, and one of the reasons the 1619 Project has provoked pointed criticism alongside praise.

Americans need to believe that, as Martin Luther King Jr. said, the arc of history bends toward justice. And they are rarely kind to those who question whether it does.

Most Americans still learn very little about the lives of the enslaved, or how the struggle over slavery shaped a young nation. Last year, the Southern Poverty Law Center found that few American high-school students know that slavery was the cause of the Civil War, that the Constitution protected slavery without explicitly mentioning it, or that ending slavery required a constitutional amendment.

“The biggest obstacle to teaching slavery effectively in America is the deep, abiding American need to conceive of and understand our history as ‘progress,’ as the story of a people and a nation that always sought the improvement of mankind, the advancement of liberty and justice, the broadening of pursuits of happiness for all,” the Yale historian David Blight wrote in the introduction to the report. “While there are many real threads to this story—about immigration, about our creeds and ideologies, and about race and emancipation and civil rights, there is also the broad, untidy underside.”

In conjunction with the Pulitzer Center, the Times has produced educational materials based on the 1619 Project for students—one of the reasons Wilentz told me he and his colleagues wrote the letter. But the materials are intended to enhance traditional curricula, not replace them. “I think that there is a misunderstanding that this curriculum is meant to replace all of U.S. history,” Silverstein told me. “It's being used as supplementary material for teaching American history." Given the state of American education on slavery, some kind of adjustment is sorely needed.

Published 400 years after the first Africans were brought to in Virginia, the project asked readers to consider “what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year.” The special issue of the Times Magazine included essays from the Princeton historian Kevin Kruse, who argued that sprawl in Atlanta is a consequence of segregation and white flight; the Times columnist Jamelle Bouie, who posited that American countermajoritarianism was shaped by pro-slavery politicians seeking to preserve the peculiar institution; and the journalist Linda Villarosa, who traced racist stereotypes about higher pain tolerance in black people from the 18th century to the present day. The articles that drew the most attention and criticism, though, were Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay chronicling black Americans’ struggle to “make democracy real” and the sociologist Matthew Desmond’s essay linking the crueler aspects of American capitalism to the labor practices that arose under slavery.

The letter’s signatories recognize the problem the Times aimed to remedy, Wilentz told me. “Each of us, all of us, think that the idea of the 1619 Project is fantastic. I mean, it's just urgently needed. The idea of bringing to light not only scholarship but all sorts of things that have to do with the centrality of slavery and of racism to American history is a wonderful idea,” he said. In a subsequent interview, he said, “Far from an attempt to discredit the 1619 Project, our letter is intended to help it.”

The letter disputes a passage in Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay, which lauds the contributions of black people to making America a full democracy and says that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery” as abolitionist sentiment began rising in Britain.

This argument is explosive. From abolition to the civil-rights movement, activists have reached back to the rhetoric and documents of the founding era to present their claims to equal citizenship as consonant with the American tradition. The Wilentz letter contends that the 1619 Project’s argument concedes too much to slavery’s defenders, likening it to South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun’s assertion that “there is not a word of truth” in the Declaration of Independence’s famous phrase that “all men are created equal.” Where Wilentz and his colleagues see the rising anti-slavery movement in the colonies and its influence on the Revolution as a radical break from millennia in which human slavery was accepted around the world, Hannah-Jones’ essay outlines how the ideology of white supremacy that sustained slavery still endures today.

“To teach children that the American Revolution was fought in part to secure slavery would be giving a fundamental misunderstanding not only of what the American Revolution was all about but what America stood for and has stood for since the Founding,” Wilentz told me. Anti-slavery ideology was a “very new thing in the world in the 18th century,” he said, and “there was more anti-slavery activity in the colonies than in Britain.”

hannah-Jones has spread this over the uS - and it is a slanted, marxist racist version of history.

Just as SR claims is not happening.

marxist history revision is happening in Schools where parents are not involved - particularly inner city warehousing schools. Teacher's colleges have been radicalized - and are radicalizing their students and in turn the kids in schools.

We may well have already have lost the battle for freedom when the young people of America are taught marxist ideals as the Fact of history.

we have been corrupted from within by our own unwillingness to stand up to the Marxist hate and Racism mongers and fomenters.

- eccielover

- 07-07-2020, 10:58 AM

THe July 4th holiday is one that is supposed to be uplifting, love for our country. Originally Posted by SpeedRacerXXXIn regards to that statement, in today's politically divisive climate(largely in my opinion due to the TDS of the left, but I'm sure your opinion on that differs), you will not find a single statement a politician can make that both sides will simultaneously take as uplifting.

You seem to like what Biden was saying, while I find it weak lead from behind rhetoric. Acquiescing to the mob of rioters and looters and proclaiming that we need change without addressing the underlying issue is divisive to me.

- bambino

- 07-07-2020, 11:05 AM

No I'm not in favor of doing anything to Mt. Rushmore. Did you read the link I cited? THe July 4th holiday is one that is supposed to be uplifting, love for our country. Trump turned the speech into a negative with comments such as this:Again, your post is YOUR opinion. I watched his speech. I didn’t think it was “divisive”. But that’s MY opinion.

The violent mayhem we have seen in the streets of cities that are run by liberal Democrats, in every case, is the predictable result of years of extreme indoctrination and bias in education, journalism, and other cultural institutions.

Against every law of society and nature, our children are taught in school to hate their own country, and to believe that the men and women who built it were not heroes, but that were villains. The radical view of American history is a web of lies — all perspective is removed, every virtue is obscured, every motive is twisted, every fact is distorted, and every flaw is magnified until the history is purged and the record is disfigured beyond all recognition.

So much BS.

Again, Trump's comments did nothing to attract undecided voters to support him. He once again pandered to his base. Originally Posted by SpeedRacerXXX

- gnadfly

- 07-07-2020, 11:34 AM