I’ve pointed this out to him several times. It just doesn’t sink in. I’m waiting for him and Lexus Lover in a cage match. I have no idea who would win. Maybe Biden could referee.

Originally Posted by bambino

maybe this will help him get it? from the far left VOX .. one of their famous (sic) "explainers" with of course the perfunctory disclaimer "NOT OBAMA'S FAULT" slant.

when VOX calls the Democratic majority lost under Obama a "collapse" it's bad.

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-polit...ats-downballot

The Democratic Party’s down-ballot collapse, explained

Thanks, Obama (well, it’s not really his fault).

By

Matthew Yglesias@mattyglesiasmatt@vox.com Jan 10, 2017

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/52672759/453866560.0.0.jpg)

(Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images)

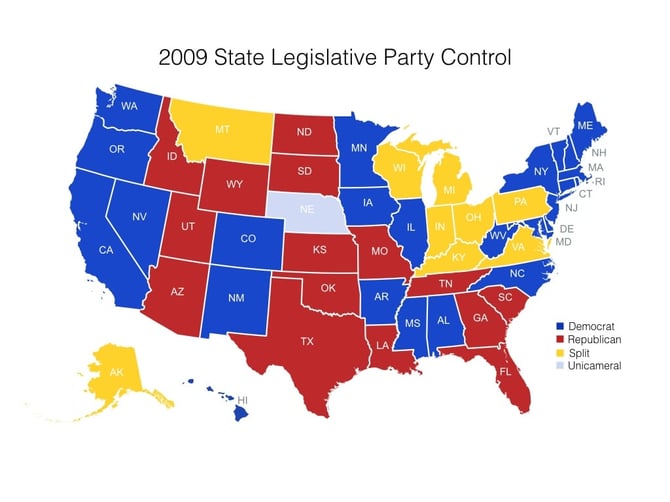

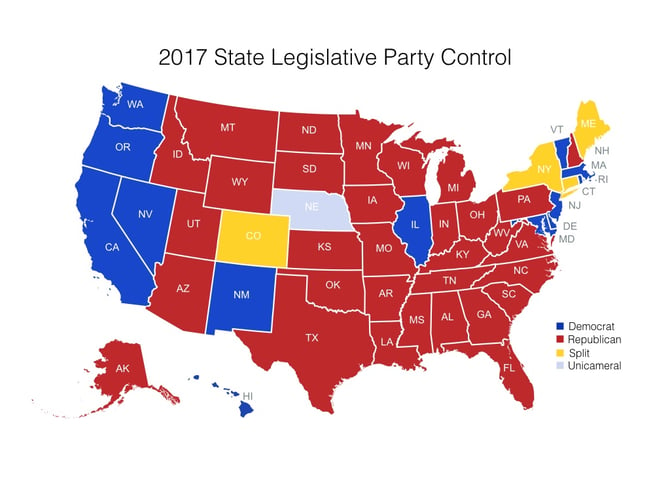

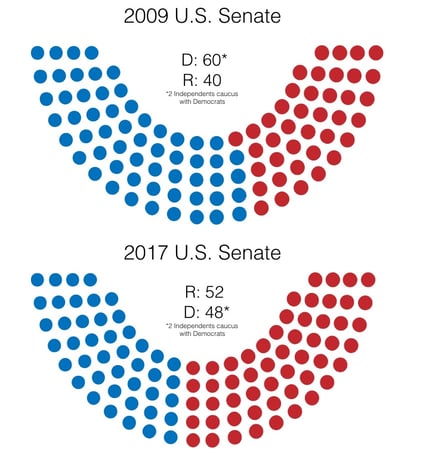

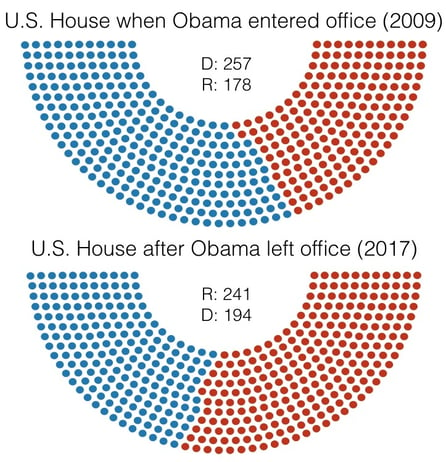

Over the past eight years, the Democratic Party has lost a mind-bogglingly large number of races across the country. Their share of seats in the United States Senate has fallen from 59 to 48. They’ve lost 62 House seats, 12 governorships, and 958 seats in state legislatures. Paired with Donald Trump’s Electoral College victory, that means that the party whose champion won the popular vote — and whose outgoing president delivers his farewell address Tuesday —

lies right now as a smoking pile of rubble.

It’s tempting to blame the man at the top — Barack Obama, whose own approval rating just hit 56 percent. To conservatives, like the Weekly Standard’s Jay Cost, the

simple moral is that “while people still like Obama, they haven't much cared for his policies — and time and again they have taken their frustrations out on his fellow partisans.” Many left critics of Obama-era policies claim the same thing. “Bernie would have won” has become a natural rallying cry for supporters of the self-proclaimed democratic socialist from Vermont.

There’s also the argument that Hillary Clinton, personally, had

serious self-confessed weaknesses as a politician and an

idiosyncratic vulnerability to an overhyped email scandal. On this version of the theory, you could just as easily say

“Gillibrand would have won” or

“O’Malley would have won” or echo Obama’s own claim that he would have

beaten Trump and won a third term. To the left, the Democrats’ down-ballot failures undermine that kind of complacency. It’s true that Obama, personally, was a very successful politician. But Obamaism, they say, has been a political failure and needs to be replaced by something new.

The truth, however, is that while it’s certainly true that

Democrats spent Obama’s last two years in office being much too complacent about the state of the party, there’s less than meets the eye regarding the apparent divergence of Obama’s political fortunes from his party’s. American politics simply operates on a very complicated series of partially overlapping time cycles — two-year House cycles, four-year presidential terms, six-year Senate terms, decennial redistricting processes — that played out in an unfavorable way for Obama-era Democrats. The party as a whole generally did well when Obama was popular (including down-ballot gains in 2016) and did poorly when he was unpopular.

But while it’s hard to blame Obama for Democrats’ down-ballot decline, it’s correct to blame him — and his team more broadly — for the complacency. Democrats were taking on water for the bulk of his presidency. And rather than act like a crew staving off emergency with an all-hands-on-deck spirit, Obamaworld largely acted like victorious conquerors and took the opportunity to cash in on the private sector.

Obama started out with a lot to lose

The most obvious problem with judging a president by a raw count of how many seats his party lost is that it serves to oddly punish Obama for Democrats’ success in 2006 and 2008. But the extreme unpopularity of George W. Bush, combined with Obama’s fresh-faced appeal and rhetorical prowess, ended up giving Obama the strongest down-ballot support of any president since Jimmy Carter.

This would almost certainly have been unsustainable under any circumstances.

The American political system features a strong tendency to revert toward the mean. You sometimes pick up unlikely seats, as when Democrats won a 2008 Senate race in Alaska or the GOP won a 2010 Senate race in Illinois, but you almost inevitably wind up giving back those gains. Had the most acute phase of the financial crisis hit in December 2008 rather than October 2008, Democrats probably would have

started Obama’s term with fewer marginal seats and therefore would have

lost less in subsequent elections.

Two-term presidents always lose down ballot

What’s more, Obama determined to put those majorities to use by pushing public policy in a more progressive direction. This has the natural consequence of costing Democrats seats because, as George Washington University’s John Sides put it in 2010,

“the public is a thermostat” and almost invariably shifts in the opposite direction from current governing trends.

“The public requests liberal policies, gets them, and then moves in the other direction,” is how Matt Grossmann, a Michigan State University political scientist, explains it. “They then get more conservative policies and move against them.”

In 2006 and 2008, the thermostat pushed many red-leaning districts to elect Democrats. The combination of a big stimulus bill, a major expansion of the welfare state, a big new financial regulation framework, and dozens of smaller initiatives was to push things in the other direction. This is simply how the system works. During the eight years of Kennedy and Johnson, Republicans made legislative gains across the country only to give them back during the eight years of Nixon and Ford.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7776149/jfkford.png) Xenocrypt

Xenocrypt

This was a turbulent 16-year span of American political history, featuring the Vietnam War, a presidential assassination, a resignation under threat of impeachment, the civil rights revolution, and much more.

But the much more placid two-term presidencies of Dwight Eisenhower and Bill Clinton show the same pattern — the only difference is Democrats didn’t make down-ballot gains in the solid South under Ike because one-party rule in Dixie was already so entrenched that there was nothing to gain.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7776169/legislatures.png) Xenocrypt

Xenocrypt

The exception that proves the rule here is the Reagan Revolution, which, whether you measure it as ending in 1989 or 1993, was associated with strong GOP gains in the South that offset losses in the North.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7776207/reagan.png) Xenocrypt

Xenocrypt

The most natural way to interpret the historical pattern is that Reagan was the beneficiary of a generational realignment of white Southerners’ partisan affiliations, not that every single other president was a miserable failure in cultivating down-ballot popularity. The fact that even Reagan generally saw GOP losses outside of the South simply underscores the strength of the overall trend.

Democrats suffered from bad timing under Obama

Obama’s boast that if he’d been on the ballot this past November he would have won is likely accurate. At the same time, if he’d been on the ballot in November 2014 he almost certainly would have lost. His intense unpopularity two years ago is now largely forgotten, since it was largely driven by two transient issues — the Ebola epidemic and a string of widely publicized ISIS beheadings — that have since vanished from the scene.

But at the time, his approval ratings were badly underwater, with only 43 percent of voters saying he was doing a good job compared with 51 percent who disapproved. This proved deadly to Democratic Party Senate candidates, who, nonetheless,

consistently outpolled Obama in their own home states.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7776483/overperform.png)

Today, Obama’s approval numbers have flipped to 56-42. Had Obama been that popular back in November 2014, it’s likely Democratic incumbents in North Carolina, Arkansas, and Louisiana would have been reelected, and there’s an outside chance Democratic challengers in Georgia and Kentucky could have prevailed.

Nothing fundamental would have to change about the long-term trajectory of American politics for that to have happened. But a 2017 reality in which Democrats held a narrow majority in the Senate — giving Democrats the ability to set the rules governing confirmation hearings and the agenda for executive branch oversight — would look very different.

By the same token, Democrats’ losses in the 2010 midterms were big, but they weren’t particularly unusual. What

was unusual is that 2010 was also a census year. Midterm elections line up with a census only once every 20 years, and while gerrymandering isn’t a new practice, the present-day combination of advanced mapping technology and ideologically sorted parties is quite new. This meant that losing ground in Obama’s first midterm election proved unusually

consequential, setting up a situation where the GOP managed to maintain its majority in the House of Representatives after the 2012 elections despite winning 1.4 million fewer votes.

Losing the White House in 2016 may have been for the best

Having done a fair amount of reporting on Democrats’ down-ballot woes over the course of 2015, I can tell you that the party’s plan for recovery didn’t really make sense. What they had was joint effort by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC), Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (DLCC), and Democratic Governors Association (DGA) to share data and field operations while identifying key districts whose underlying demographics were shifting in a more blue-friendly direction. Their hope was to make gains in 2016, minimize losses in 2018, and then make a big push to win state legislatures in 2020 in order to control the redistricting process.

This was pretty much the best plan available to them, but it stood no real chance of working. There’s simply no precedent for a party making those kinds of big down-ballot gains while holding the White House.

Over the summer of 2016, something else unprecedented happened, as Donald Trump secured the GOP nomination and at a couple of junctures appeared to be headed for a huge landslide defeat. Instead, he successfully reconsolidated the support of just enough traditionally Republican-voting white college graduates in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania to eke out an Electoral College win while losing the popular vote.

Democrats rightly regard this as an alarming development both for their party’s issue agenda and for the stability of American democratic institutions. But from a narrow party-building perspective, it gives them a much more realistic chance at recovery.

Faced with the objective problem of unfavorably drawn districts for both the House of Representatives and most state legislatures, the best solution is the opportunity to run against an unpopular incumbent president. There’s obviously no guarantee that Trump

will be unpopular in 2018 and 2020. But having an incumbent president of the other party to run against is the necessary first step, and at the moment Trump is unusually unpopular for a president-elect who’s supposed to be enjoying his honeymoon period.

Obama hasn’t been much of a party builder

While much of the above has tended in the direction of exculpating Obama from blame for the sorry state of his party, the basic numbers are bad enough that it’s unavoidable to cast some blame in the direction of the outgoing president and his team.

This starts with the matter of the succession. Hillary Clinton’s weaknesses as a general election candidate were not unforeseeable. Indeed, the ability to foresee them was one of the main reasons Obama was able to garner endorsements from so many party elected officials back in his 2008 primary campaign. But starting with his selection of a vice president who, though well-liked, did not seem to inspire enormous confidence in Obama as a potential president, Obama consistently acted to make Clinton his designated successor in all but name. This began well before the 2016 primary season officially started, and contributed to the pace with which the field narrowed down to a Clinton-versus-Sanders choice.

Nor has Obama been particularly astute in using executive branch appointments to elevate the profiles of talented younger people who might make effective electoral candidates. Someone like Housing and Urban Development Secretary JuliŠn Castro is frequently seen as a “rising star” pick in this mold, but Castro is from Texas, where close association with a Democratic administration in Washington is unlikely to be helpful. By contrast, there are states that Obama won twice, like Florida, Wisconsin, and Michigan, whose local parties are hurting for talent with name recognition and fundraising ability.

Most of all, the Obama team often contributed to — and seemed complicit in — an atmosphere of complacency, in which control of the White House obscured the Democratic Party’s underlying weaknesses. Losing to Trump, who was an unusually poor candidate, was a bitter pill to swallow. But Democrats were lucky to face off against a weak nominee in a year when the fundamentals favored a GOP victory.

A very large share of veterans of the Obama White House — people who’d come to Washington because they cared about issues and causes — ended up cycling out to the private sector, often in Silicon Valley or Wall Street, even though the legacy they’d fought for was far from secure. The prevailing attitude seemed to be that continuing the fight in Congress or in the states — whether that meant helping Democrats win back states where they’d lost control or simply helping Democratic governors of blue states succeed in building inspiring models of progressive politics — was unnecessary.

Trump’s victory is already beginning to push some Obama veterans back into the game with, for example, the team behind the Keepin’ It 1600 podcast mostly quitting their day jobs to form a new media company. The underlying weaknesses that Trump’s win exposed were caused much more by bad timing than anything about Obama personally or ideologically. But it’s been present and clearly visible for at least two if not six years, yet it’s only over the past month or so that Obamaworld seems to have become fully awake to it.

.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/52672759/453866560.0.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7776149/jfkford.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7776169/legislatures.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7776207/reagan.png)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7776483/overperform.png)