- watchoutthegameisrigged

- 02-12-2017, 12:24 AM

Well where the fuck else? You are ridiculous. Tell us all, please, what ever the fuck you want to tell us. No criptic BS, lay it out.

- MrGiz

- 02-12-2017, 12:58 AM

He's just trying to boost sells for Felina while putting everyone else down. He complains about WKs while being one himself. It's pitiful. Ignore him. He'll get bored and go away. Originally Posted by Danielle ReidWho has EVER mentioned Felina, BESIDES YOU????

I challenge ANYONE to even INSINUATE, that I have EVER favored ANY girl over another...EVER!!!

- Miss Dreams... So Many Times... Definition Of A Sweetheart

- Nikki Tylor, (finest female in the Universe) again and again and again...

- Julinka... same ......... The Ninth Wonder of The World!!

- Jade / SknyDiva. . . My "other" Girlfriend

- April Cox

- Starla Jones

- Tori Ashton

- Diamond

- Daivya

- Taylor Fox

- KateSpinner

- Junesetx

- Keri2114 / New Orleans

- Ambersilk

- Anastasia

- Angie of Baton Rouge

- Ark Monroe

- Tara Blonde

- Jewels

- Ginger Doll

- Jessika Sweetz

- Sweet Mellissa (gulf coast)

- Miss Melissa

- Brittany715

- Sweet Melissa

- Kelly / Special K

- Lexi Love

- Celeth

- Shannon / Savannah /Strip Dancing Queen

- Charisma Creams

- Lacey Amour

- Stacey Martin

- Molly Morgen

- Kristen DiAngelo

- Gemini Starr

- Madalyn Grace

- Lirette

- Elegance Reign

- Garcelle Duvalier (the absolute best fuck of my life) repeatedly....

- Taylor Love

- Kinky Little Nikki / KLN

- Dallas rain

- Robyn

- Hot Springs Fairy/Nyki

- Cashmyre

- Pamalatoo

- So So So So Many More... Around the Entire Globe

I've enjoyed more females than Arkansas even has a clue that ever existed... and a SCUMBAG like YOU is going to pick out "ONE" of your competitors to "NAME" in public??????

REALLY????

You Have Just Proven What Kind Of Trash You Are!!

You have obviously, spent too much time in the Hot Tub!!

-

- Guest110920

- 02-12-2017, 01:12 AM

Mods, you might as well lock this thread. It was nice and friendly before the troublemakers showed up but clearly that will no longer be the case.

- MrGiz

- 02-12-2017, 01:17 AM

Mods, you might as well lock this thread. It was nice and friendly before the troublemakers showed up but clearly that will no longer be the case. Originally Posted by SpankyJI thought you were on "Ignore"!!

How many other LIARS do we have in this thread?

Danielle Reid needs to be BANNED, NOW !!

- Ginger Doll

- 02-12-2017, 02:04 AM

I think after being unnecessarily subjected to a bunch of negative bullshit, everyone could use a video of a cute puppy.

- MrGiz

- 02-12-2017, 02:17 AM

.... after being unnecessarily subjected to a bunch of negative bullshit, everyone could use a good dose of truth & reality! Originally Posted by Ginger Doll

- Guest110920

- 02-12-2017, 07:20 AM

I thought you were on "Ignore"!!I could, see that you...were still, posting...and couldn't...stand not knowing, how you would, creatively misuse...commas and ellipsis..NEXT!!!

How many other LIARS do we have in this thread?

Danielle Reid needs to be BANNED, NOW !! Originally Posted by NTJME

Enjoy your thread crapping. It was a good thread until you arrived to fuck it up for everyone.

- Guest110920

- 02-12-2017, 07:32 AM

A troll is a class of being in Norse mythology and Scandinavian folklore. In Old Norse sources, beings described as trolls dwell in isolated rocks, mountains, or caves, live together in small family units, and are rarely helpful to human beings.

Later, in Scandinavian folklore, trolls became beings in their own right, where they live far from human habitation, are not Christianized, and are considered dangerous to human beings. Depending on the source, their appearance varies greatly; trolls may be ugly and slow-witted, or look and behave exactly like human beings, with no particularly grotesque characteristic about them.

Trolls are sometimes associated with particular landmarks, which at times may be explained as formed from a troll exposed to sunlight. Trolls are depicted in a variety of media in modern popular culture.

The Old Norse nouns troll and tröll (variously meaning 'fiend, demon, werewolf, jötunn') and Middle High German troll, trolle 'fiend' (according to philologist Vladimir Orel likely borrowed from Old Norse) developed from Proto-Germanic neuter noun *trullan. The origin of the Proto-Germanic word is unknown.[1] Additionally, the Old Norse verb trylla 'to enchant, to turn into a troll' and the Middle High German verb trüllen 'to flutter' both developed from the Proto-Germanic verb *trulljanan, a derivative of *trullan.[1]

In Norse mythology, troll, like thurs, is a term applied to jötnar and is mentioned throughout the Old Norse corpus. In Old Norse sources, trolls are said to dwell in isolated mountains, rocks, and caves, sometimes live together (usually as father-and-daughter or mother-and-son), and are rarely described as helpful or friendly.[2] The Prose Edda book Skáldskaparmál describes an encounter between an unnamed troll woman and the 9th century skald Bragi Boddason. According to the section, Bragi was driving through "a certain forest" late one evening when a troll woman aggressively asked him who he was, in the process describing herself:

Old Norse:

Troll kalla miktrungl sjǫtrungnis,auđsug jǫtuns,élsólar bǫl,vilsinn vǫlu,vǫrđ nafjarđar,hvélsveg himins –hvat's troll nema ţat?[3] Anthony Faulkes translation:

'Trolls call memoon of dwelling-Rungnir,giant's wealth-sucker,storm-sun's bale,seeress's friendly companion,guardian of corpse-fiord,swallower of heaven-wheel;what is a troll other than that?'[4] John Lindow translation:

They call me a troll,moon of the earth-Hrungnir [?]wealth sucker [?] of the giant,destroyer of the storm-sun [?]beloved follower of the seeress,guardian of the "nafjord" [?]swallower of the wheel of heaven [the sun].What's a troll if not that?[3]

Bragi responds in turn, describing himself and his abilities as a skillful skald, before the scenario ends.[4]

There is much confusion and overlap in the use of Old Norse terms jötunn, troll, ţurs, and risi, which describe various beings. Lotte Motz theorized that these were originally four distinct classes of beings: lords of nature (jötunn), mythical magicians (troll), hostile monsters (ţurs), and heroic and courtly beings (risi), the last class being the youngest addition. On the other hand, Ármann Jakobson is critical of Motz's interpretation and calls this theory "unsupported by any convincing evidence".[5] Ármann highlights that the term is used to denote various beings, such as a jötunn or mountain-dweller, a witch, an abnormally strong or large or ugly person, an evil spirit, a ghost, a blámađr, a magical boar, a heathen demi-god, a demon, a brunnmigi, or a berserker.[6]

Later in Scandinavian folklore, trolls become defined as a particular type of being.[7] Numerous tales are recorded about trolls in which they are frequently described as being extremely old, very strong, but slow and dim-witted, and are at times described as man-eaters and as turning to stone upon contact with sunlight.[8] However, trolls are also attested as looking much the same as human beings, without any particularly hideous appearance about them, but living far away from human habitation and generally having "some form of social organization" — unlike the rĺ and näck, who are attested as "solitary beings". According to John Lindow, what sets them apart is that they are not Christian, and those who encounter them do not know them. Therefore, trolls were in the end dangerous, regardless of how well they might get along with Christian society, and trolls display a habit of bergtagning ('kidnapping'; literally "mountain-taking") and overrunning a farm or estate.[9]

Lindow states that the etymology of the word "troll" remains uncertain, though he defines trolls in later Swedish folklore as "nature beings" and as "all-purpose otherworldly being[s], equivalent, for example, to fairies in Anglo-Celtic traditions". They "therefore appear in various migratory legends where collective nature-beings are called for". Lindow notes that trolls are sometimes swapped out for cats and "little people" in the folklore record.[9]

A Scandinavian folk belief that lightning frightens away trolls and jötnar appears in numerous Scandinavian folktales, and may be a late reflection of the god Thor's role in fighting such beings. In connection, the lack of trolls and jötnar in modern Scandinavia is sometimes explained as a result of the "accuracy and efficiency of the lightning strokes".[10] Additionally, the absence of trolls in regions of Scandinavia are described in folklore as being a "consequence of the constant din of the church-bells". This ring caused the trolls to leave for other lands, although not without some resistance; numerous traditions relate how trolls destroyed a church under construction or hurled boulders and stones at completed churches. Large local stones are sometimes described as the product of a troll's toss.[11] Additionally, into the 20th century, the origins of particular Scandinavian landmarks, such as particular stones, are ascribed to trolls who may, for example, have turned to stone upon exposure to sunlight.[8]

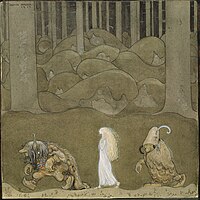

The Princess and the Trolls –The Changeling, by John Bauer, 1913.

Lindow compares the trolls of the Swedish folk tradition to Grendel, the supernatural mead hall invader in the Old English poem Beowulf, and notes that "just as the poem Beowulf emphasizes not the harrying of Grendel but the cleansing of the hall of Beowulf, so the modern tales stress the moment when the trolls are driven off."[9]

Smaller trolls are attested as living in burial mounds and in mountains in Scandinavian folk tradition.[12] In Denmark, these creatures are recorded as troldfolk ("troll-folk"), bjergtrolde ("mountain-trolls"), or bjergfolk ("mountain-folk") and in Norway also as troldfolk ("troll-folk") and tusser.[12] Trolls may be described as small, human-like beings or as tall as men depending on the region of origin of the story.[13]

In Norwegian tradition, similar tales may be told about the larger trolls and the Huldrefolk ("hidden-folk") yet a distinction is made between the two. The use of the word trow in Orkney and Shetland, to mean beings which are very like the Huldrefolk in Norway may suggest a common origin for the terms. The word troll may have been used by pagan Norse settlers in Orkney and Shetland as a collective term for supernatural beings who should be respected and avoided rather than worshiped. Troll could later have become specialized as a description of the larger, more menacing Jötunn-kind whereas Huldrefolk may have developed as the general term applied to smaller trolls.[14]

John Arnott MacCulloch posited a connection between the Old Norse vćttir and trolls, suggesting that both concepts may derive from spirits of the dead.[15]

References

See also: NTJME

Later, in Scandinavian folklore, trolls became beings in their own right, where they live far from human habitation, are not Christianized, and are considered dangerous to human beings. Depending on the source, their appearance varies greatly; trolls may be ugly and slow-witted, or look and behave exactly like human beings, with no particularly grotesque characteristic about them.

Trolls are sometimes associated with particular landmarks, which at times may be explained as formed from a troll exposed to sunlight. Trolls are depicted in a variety of media in modern popular culture.

The Old Norse nouns troll and tröll (variously meaning 'fiend, demon, werewolf, jötunn') and Middle High German troll, trolle 'fiend' (according to philologist Vladimir Orel likely borrowed from Old Norse) developed from Proto-Germanic neuter noun *trullan. The origin of the Proto-Germanic word is unknown.[1] Additionally, the Old Norse verb trylla 'to enchant, to turn into a troll' and the Middle High German verb trüllen 'to flutter' both developed from the Proto-Germanic verb *trulljanan, a derivative of *trullan.[1]

In Norse mythology, troll, like thurs, is a term applied to jötnar and is mentioned throughout the Old Norse corpus. In Old Norse sources, trolls are said to dwell in isolated mountains, rocks, and caves, sometimes live together (usually as father-and-daughter or mother-and-son), and are rarely described as helpful or friendly.[2] The Prose Edda book Skáldskaparmál describes an encounter between an unnamed troll woman and the 9th century skald Bragi Boddason. According to the section, Bragi was driving through "a certain forest" late one evening when a troll woman aggressively asked him who he was, in the process describing herself:

Old Norse:

Troll kalla miktrungl sjǫtrungnis,auđsug jǫtuns,élsólar bǫl,vilsinn vǫlu,vǫrđ nafjarđar,hvélsveg himins –hvat's troll nema ţat?[3] Anthony Faulkes translation:

'Trolls call memoon of dwelling-Rungnir,giant's wealth-sucker,storm-sun's bale,seeress's friendly companion,guardian of corpse-fiord,swallower of heaven-wheel;what is a troll other than that?'[4] John Lindow translation:

They call me a troll,moon of the earth-Hrungnir [?]wealth sucker [?] of the giant,destroyer of the storm-sun [?]beloved follower of the seeress,guardian of the "nafjord" [?]swallower of the wheel of heaven [the sun].What's a troll if not that?[3]

Bragi responds in turn, describing himself and his abilities as a skillful skald, before the scenario ends.[4]

There is much confusion and overlap in the use of Old Norse terms jötunn, troll, ţurs, and risi, which describe various beings. Lotte Motz theorized that these were originally four distinct classes of beings: lords of nature (jötunn), mythical magicians (troll), hostile monsters (ţurs), and heroic and courtly beings (risi), the last class being the youngest addition. On the other hand, Ármann Jakobson is critical of Motz's interpretation and calls this theory "unsupported by any convincing evidence".[5] Ármann highlights that the term is used to denote various beings, such as a jötunn or mountain-dweller, a witch, an abnormally strong or large or ugly person, an evil spirit, a ghost, a blámađr, a magical boar, a heathen demi-god, a demon, a brunnmigi, or a berserker.[6]

Later in Scandinavian folklore, trolls become defined as a particular type of being.[7] Numerous tales are recorded about trolls in which they are frequently described as being extremely old, very strong, but slow and dim-witted, and are at times described as man-eaters and as turning to stone upon contact with sunlight.[8] However, trolls are also attested as looking much the same as human beings, without any particularly hideous appearance about them, but living far away from human habitation and generally having "some form of social organization" — unlike the rĺ and näck, who are attested as "solitary beings". According to John Lindow, what sets them apart is that they are not Christian, and those who encounter them do not know them. Therefore, trolls were in the end dangerous, regardless of how well they might get along with Christian society, and trolls display a habit of bergtagning ('kidnapping'; literally "mountain-taking") and overrunning a farm or estate.[9]

Lindow states that the etymology of the word "troll" remains uncertain, though he defines trolls in later Swedish folklore as "nature beings" and as "all-purpose otherworldly being[s], equivalent, for example, to fairies in Anglo-Celtic traditions". They "therefore appear in various migratory legends where collective nature-beings are called for". Lindow notes that trolls are sometimes swapped out for cats and "little people" in the folklore record.[9]

A Scandinavian folk belief that lightning frightens away trolls and jötnar appears in numerous Scandinavian folktales, and may be a late reflection of the god Thor's role in fighting such beings. In connection, the lack of trolls and jötnar in modern Scandinavia is sometimes explained as a result of the "accuracy and efficiency of the lightning strokes".[10] Additionally, the absence of trolls in regions of Scandinavia are described in folklore as being a "consequence of the constant din of the church-bells". This ring caused the trolls to leave for other lands, although not without some resistance; numerous traditions relate how trolls destroyed a church under construction or hurled boulders and stones at completed churches. Large local stones are sometimes described as the product of a troll's toss.[11] Additionally, into the 20th century, the origins of particular Scandinavian landmarks, such as particular stones, are ascribed to trolls who may, for example, have turned to stone upon exposure to sunlight.[8]

The Princess and the Trolls –The Changeling, by John Bauer, 1913.

Lindow compares the trolls of the Swedish folk tradition to Grendel, the supernatural mead hall invader in the Old English poem Beowulf, and notes that "just as the poem Beowulf emphasizes not the harrying of Grendel but the cleansing of the hall of Beowulf, so the modern tales stress the moment when the trolls are driven off."[9]

Smaller trolls are attested as living in burial mounds and in mountains in Scandinavian folk tradition.[12] In Denmark, these creatures are recorded as troldfolk ("troll-folk"), bjergtrolde ("mountain-trolls"), or bjergfolk ("mountain-folk") and in Norway also as troldfolk ("troll-folk") and tusser.[12] Trolls may be described as small, human-like beings or as tall as men depending on the region of origin of the story.[13]

In Norwegian tradition, similar tales may be told about the larger trolls and the Huldrefolk ("hidden-folk") yet a distinction is made between the two. The use of the word trow in Orkney and Shetland, to mean beings which are very like the Huldrefolk in Norway may suggest a common origin for the terms. The word troll may have been used by pagan Norse settlers in Orkney and Shetland as a collective term for supernatural beings who should be respected and avoided rather than worshiped. Troll could later have become specialized as a description of the larger, more menacing Jötunn-kind whereas Huldrefolk may have developed as the general term applied to smaller trolls.[14]

John Arnott MacCulloch posited a connection between the Old Norse vćttir and trolls, suggesting that both concepts may derive from spirits of the dead.[15]

References

- Ármann Jakobsson (2006). "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Bárđar saga and Its Giants" in The Fantastic in Old Norse/Icelandic Literature, pp. 54–62. Available online at dur.ac.uk (archived version from March 4, 2007)

- Ármann Jakobsson (2008). "The Trollish Acts of Ţorgrímr the Witch: The Meanings of Troll and Ergi in Medieval Iceland" in Saga-Book 32 (2008), 39–68.

- Kvideland, Reimund. Sehmsdorf, Henning K. (editors) (2010). Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1967-2

- Lindow, John (1978). Swedish Folktales and Legends. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03520-8

- Lindow, John (2007). "Narrative Worlds, Human Environments, and Poets: The Case of Bragi" as published in Andrén, Anders. Jennbert, Kristina. Raudvere, Catharina. Old Norse Religion in Long-Term Perspectives. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 978-91-89116-81-8 (google book)

- MacCulloch, John Arnott (1930). Eddic Mythology, The Mythology of All Races In Thirteen volumes, Vol. II. Cooper Square Publishers. PDF version online.

- Narváez, Peter (1997). The Good People: New Fairylore Essays (The pages referenced are from a paper by Alan Bruford entitled "Trolls, Hillfolk, Finns, and Picts: The Identity of the Good Neighbors in Orkney and Shetland"). University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-0939-8

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Orel, Vladimir (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Brill. ISBN 9004128751

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer ISBN 0-85991-513-1

- Thorpe, Benjamin (1851). Northern Mythology, Compromising the Principal Traditions and Superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and the Netherlands: Compiled from Original and Other Sources. In three Volumes. Scandinavian Popular Traditions and Superstitions, Volume 2. Lumley.

See also: NTJME

- Guest110920

- 02-12-2017, 07:54 AM

I think after being unnecessarily subjected to a bunch of negative bullshit, everyone could use a video of a cute puppy.Thank you, that was so cute!

Originally Posted by Ginger Doll

- Danielle Reid

- 02-12-2017, 09:13 AM

You Have Just Proven What Kind Of Trash You Are!!

You have obviously, spent too much time in the Hot Tub!!

Originally Posted by NTJME

- Danielle Reid

- 02-12-2017, 09:15 AM

Call me Mrs. Grouch

- yeahthatguy

- 02-12-2017, 04:47 PM

Well this seems to have gotten much less 'random', hasn't it? (wow)

And now for something completely different...

Did you know that most people have enough bones in their bodies to make a complete skeleton?

And now for something completely different...

Did you know that most people have enough bones in their bodies to make a complete skeleton?

- Ginger Doll

- 02-12-2017, 04:55 PM

Thank you, that was so cute! Originally Posted by SpankyJRandom announcement. After repeatedly watching the adorable golden retriever video, I am now thinking about buying one. Ed needs a 4-legged friend.

- Guest110920

- 02-12-2017, 05:53 PM

Well this seems to have gotten much less 'random', hasn't it? (wow)Also the average person has less than two arms and two legs. Actually the intersection set between those with less than 2 arms and legs and those with less bones in their body than needed to make a complete skeleton is probably pretty sizable!

And now for something completely different...

Did you know that most people have enough bones in their bodies to make a complete skeleton? Originally Posted by yeahthatguy

- Guest110920

- 02-12-2017, 06:04 PM

Originally Posted by Ginger Doll

Originally Posted by Ginger Doll