- OldGent

- 01-29-2017, 06:50 AM

Agreed Brother Kwin. Stay tuned for some of those zones in my double review of her and Lily Kat. And thanks for being part of history. You rock dude.

- Lena Duvall

- 01-31-2017, 08:58 AM

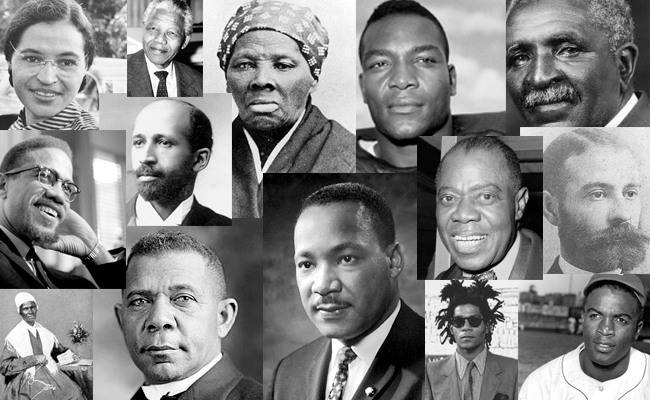

Black History Month starts tomorrow.

Let's make the most of all 28 days.

Let's make the most of all 28 days.

- Guest123018

- 02-01-2017, 10:26 AM

Even though I started early. ..

Happy 1st day of

Black History Month

Happy 1st day of

Black History Month

- Lily Kat Wood

- 02-01-2017, 01:24 PM

Democracy

Democracy will not come

Today, this year

Nor ever

Through compromise and fear.

I have as much right

As the other fellow has

To stand

On my two feet

And own the land.

I tire so of hearing people say,

Let things take their course.

Tomorrow is another day.

I do not need my freedom when I'm dead.

I cannot live on tomorrow's bread.

Freedom

Is a strong seed

Planted

In a great need.

I live here, too.

I want freedom

Just as you.

Langston Hughes

Democracy will not come

Today, this year

Nor ever

Through compromise and fear.

I have as much right

As the other fellow has

To stand

On my two feet

And own the land.

I tire so of hearing people say,

Let things take their course.

Tomorrow is another day.

I do not need my freedom when I'm dead.

I cannot live on tomorrow's bread.

Freedom

Is a strong seed

Planted

In a great need.

I live here, too.

I want freedom

Just as you.

Langston Hughes

- Lily Kat Wood

- 02-01-2017, 01:33 PM

I love this!!!

- OldGent

- 02-01-2017, 02:13 PM

Mary Ellen Pleasant

We don’t know much about Mary Ellen Pleasant. Much has been said, though, and even more implied. Without a doubt, there were many interesting facets to the life of the woman who was called one of the richest black women in America in the 1860s.Pleasant’s mother told her that she was the daughter of a white plantation owner and belonged to a long line of “Voodoo Queens” from Santo Domingo. When she was 11, she was sold to a man in New Orleans, who sent her to a convent to be educated and then given her freedom. Much of her early life was spent traveling the East Coast, and by the 1840s, she and her husband, James Smith, were active in smuggling hundreds of slaves to freedom. She trained as a cook to infiltrate plantations, but when suspicions started to grow, she hopped on a ship, sailed around the world, and ended up in San Francisco. (Another version of the story has her getting to California via sailing to Panama, walking to the Pacific, and then taking a ship north.)In San Francisco, Pleasant became the adviser to Thomas Bell, one of the directors of the Bank of California. Just what else she did has been up to speculation. According to some accounts, she groomed young women for marriage to wealthy men. Other stories have her running a chain of bordellos, claiming that she would invest in real estate and turn the buildings into boardinghouses. Those boardinghouses would be full of clients, and she reportedly set up women with wealthy white clients for a night or for a lifetime. One of her “proteges” eventually married Thomas Bell. The gratitude was short-lived, however, as when Bell died in 1892, his wife threw Pleasant out onto the street. Pleasant had been living with them as their maid, although some reports suggest that they had been the ones living with her. While Pleasant ran her businesses, she acted as a staunch abolitionist. In 1858, she contributed $30,000 to help fund John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, and she even took a streetcar company to court for refusing to let her sit. She won, and throughout the 1860s, her influence was undeniable. She was well-known (through rumors) as the person who could find someone a wife or find homes for the illegitimate children that came from extramarital dalliances.

- annie@christophers

- 02-01-2017, 03:23 PM

ya know March 17th we pray to a higher God righr* ON THE KNEES BOY..XXOO QUALITY

- MOCHAakaMOCHA

- 02-01-2017, 05:41 PM

Whew!

- Lena Duvall

- 02-02-2017, 08:25 AM

Yaaaaasss!

Keep it going everyone.

Keep it going everyone.

- myren1900

- 02-05-2017, 06:27 PM

- R.M.

- 02-05-2017, 10:20 PM

- Lily Kat Wood

- 02-06-2017, 06:54 PM

On June 7, 1892, at Royal and Press streets, Homer Plessy bought a ticket in New Orleans for a Covington-bound train. As he climbed into a car reserved for white people, he braced for trouble. In fact, he was counting on it. Plessy -- a Creole shoemaker of color -- was arrested and, with the backing of the New Orleans-based Comite des Citoyens (Citizens Committee), ignited a case that would lead to the landmark Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld racial segregation for 62 years.

The Plessy v. Ferguson case was one of the first uses of the equal protection provision of the 14 th Amendment to challenge segregation. As such, it is recognized as a key moment in the civil rights struggles to come in the 20 th century. In addition to having a New Orleans school named after him, a plaque at Royal and Press streets marks the spot of the train station at which Plessy was arrested. Another marks the Plessy tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1

Plessy was charged with violating the state's controversial Separate Car Act, which mandated separate rail cars for black and white travelers. His court-ordered punishment? A $25 fine or 20 days in jail.

Plessy and the Citizens Committee weren't the only ones who opposed the Separate Car Act. So did the East Louisiana Railroad Co., which saw maintaining separate cars as a fiscal burden. For that reason, the committee let the railroad know in advance what they were planning and to make sure a conductor challenged him.

Leaving nothing to chance, the committee also hired a private detective with arrest powers to take Plessy into custody, ensuring he was booked with violating the Separate Car Act -- the law they hoped to test -- instead of another misdemeanor.

Plessy lost his Supreme Court case, with the court's 7-1 ruling upholding "separate but equal" statutes and giving legal cover to the Jim Crow laws that would govern the majority of the 20 th century. But the strategy displayed by Plessy and the Comite des Citoyens in their highly orchestrated act of civil disobedience laid the foundation for future civil rights battles to come. Sixty-two years later, Brown vs. the Board of Education would finally overturn "separate but equal," thanks in no small part to the fight started at Royal and Press streets by Homer Plessy.

- OldGent

- 02-09-2017, 02:33 PM

- Melissa Madyson

- 02-09-2017, 03:13 PM

- pyramider

- 02-09-2017, 07:56 PM

No black taint photos? Its Black History Month!!